Applying a bit of pedagogy theory for better kendo instruction : giving purpose and using the deductive approach.

It’s not a new idea, back in 2012, I had already noted in my dissertation towards my pedagogy degree, that the way Kendo is taught often fails to motivate learners for orthodoxy’s sake.

A sense of purpose is rarely given to beginners and they are simply expected to perform tasks and drills without knowing their goal in the long run. Not all dojos teach like that, of course, but I’d be willing to risk myself stating that it’s pretty much the rule out there.

In the minds of some western instructors, the ideas of training à la Japanese, including the harsh treatment and the philosophy of “出る釘は打たれる” (the nail that sticks out gets hammered down) inhabit most of western kenshis’ imaginations as exotic traits that are desired and sometimes almost romanticised.

But many things go wrong and get lost in the translation because we interpret another culture with our own frame of reference without really trying to understand what makes us different and therefore should warrant (at least slightly) different approaches.

For example, westerners’ concept of discipline is deeply militaristic, and with armies come stupidity, yelling orders, “If I ask you to jump, you say how high!” it also brings along its potential share of humiliations, hazings, etc.

Seen through that scope, one could mistake the Japanese tendency to withdraw the ego in favour of the group — a trait acquired from a very young age that has its base in learning respect for each other and for the places we live in — for our own western conception of obedience and discipline.

I bet every western federation has an iteration of that instructor who’s on a narcissistic ego trip that leads to abusive behaviours within their dojo but no one bats an eye because “IT’S JAPANESE DISCIPLINE”.

One might tell me “but the Imperial Guard and Police are like that” but since both of those are militaristic organisations, it kinda proves my point, not to mention the fact that we, as westerners tend to admire that kendo, maybe specifically, because it meets our collective subconscious’ expectations of strict discipline.

Anyway, you might have heard some fellow kenshi utter the phrase “let us not think that we are more Japanese than the Japanese themselves”. This is a sentence that aims at avoiding the problem by stating that one shouldn’t try to emulate everything mindlessly, without critical thinking.

In my opinion, this also has to apply to the teaching method.

(Because believe it or not, I wasn’t going to talk about abuse at all).

——

The importance of purpose.

Pedagogy theory tells us that adult learners, and probably voluntary learners in general, engage into a learning process, motivated by a goal, an outcome. There is a strong need from learners to know that what they are learning is useful. The relevance of learning a specific skill must be clear to them in relation to the general goal.

In kendo, the importance of this might be often overlooked, as the learning process is akin to the inductive approach, where from learning specific actions or skills, a learner is supposed to piece together by and for himself the general mechanics of kendo. In the context of a classroom, it is an approach that is usually preferred, because there is constant dialog and (co)building of the knowledge. But in the context of kendo and its solitary element, it is a pretty daunting task for most.

The deductive method, going from the general idea towards specific skills that are clearly seen as necessary by the learner is often times better suited to maintain the motivation of the beginner as well as (counter intuitively) giving them the tools to look after their own evolution.

This might seem a bit obscure, but I have an example for you, using the difficult-to-grasp notion of seme :

The way I was first taught seme was simply through the instructions “step in, take the center, strike” without much else to go on. I understood the drill and could see how it could work in theory, but in practice, it isn’t easy to pull off, I had to figure out the general mechanics for myself and it took me quite a few years to understand the general idea behind seme.

That’s the inductive approach. “From separate drills and not much linking context, go and discover the secrets behind seme my young Padawan!”

The counter-example :

This season, with shinsa coming for many of my members, I’ve searched for ways to make the bigger principles as clear as possible in the least amount of words and after a few training sessions, I’m finding myself believing that Kizeme (threat through your “energy”), which we often see as most complicated, is actually the type of seme that contains the general principle and therefore could be most relevant as a starting point.

Make yourself tall, relax, don’t let aite impress you, don’t step backwards, show that you are there and willing, as if you were telling aite “I’m here, I’m not going anywhere, watchu gonna do about it”.

That would be complicated only if you were thinking about learning specific actions, but if you have a wider approach with a clear goal in mind, it is actually easy to make the learners understand how that plays out.

Then, knowing the purpose and the goal that is being aimed that, going into a specific drill like “take center, strike men” becomes so much more meaningful for the learners. It is not only learning the moves behind the technique, but learning the moves of a technique within its proper context.

To sum it up : for maximised motivation and efficiency, learners should always know the following points and the instructor should make it clear for them in this order :

- This is the goal (i.e. “we are working on becoming proficient at seme”)

- This is the canvas (i.e. “seme is about the pressure on the other and putting ourselves in a favourable spot for attacks that will lead to ippon” — the importance of the general principle should be made clear)

- These are the drills to achieve the goal within the canvas (i.e. from the simple “step-in to take center and strike immediately” to the more subtle hikidasu, all depend on the learner’s ability to have a strong presence and a mind geared towards meeting/attacking the opponent)

Then all an instructor would have to do is keeping learners motivated and putting on them the responsibility of keeping these aspects in mind while going through the drills.

Once the method is correctly implemented (and why not, explained) learners can become their own day-to-day instructors and more efficiently identify their flaws, the areas that need their attention as well as purposefully setting goals for themselves.

That’s how I’ve been going about my own training anyway, but through experimentation and lots of trials and errors. As a dojo-leader, I’m happy to be able to put my formal pedagogy training to good use in helping others go over obstacles faster than I did.

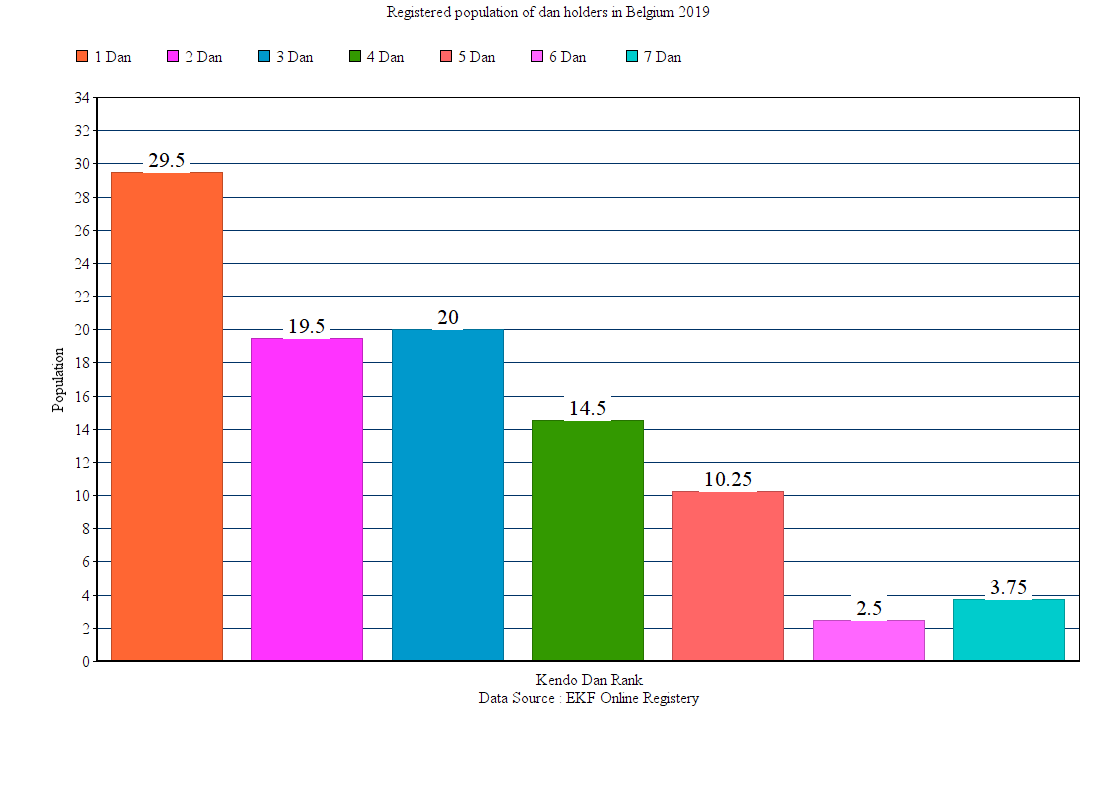

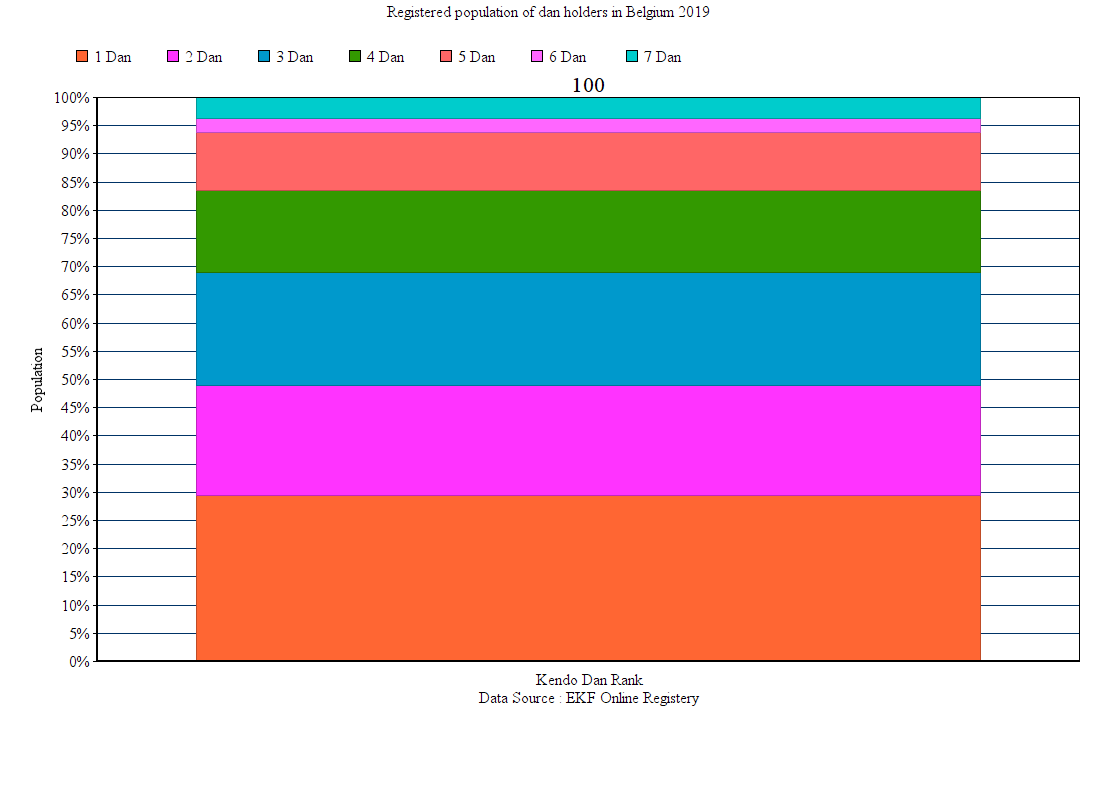

Belgium has this noticeable particularity of having a high concentration of K7s, at almost 4% of the total yudansha population. For a small federation like us it’s quite remarkable (12 out of 321)

Belgium has this noticeable particularity of having a high concentration of K7s, at almost 4% of the total yudansha population. For a small federation like us it’s quite remarkable (12 out of 321)